My Journey with Alcohol

For my father. I wish I’d got free soon enough to come back for you.

OK, so, some new friends come over for dinner. I have cooked a nice steak. My wife pulls a bottle of red wine out of the cupboard and say, “We don’t really drink, but would you like some pinot noir with your steak?.”

Uncomfortable glances between them… What’s the protocol here? “Oh, you don’t drink? Do you want us to not drink around you? Because we don’t drink that much and we can certainly forgo booze for a single meal if it’ll make you more comfortable.”

These folks are just trying to be polite and sociable, and suddenly they’re stuck in a quandary of trying to be supportive about an unknown addiction status, without actually implying that anyone present has a drinking problem.

I grab the bottle and pour a small glass: “It’s really just a preference. Alcohol just doesn’t vibe with my body anymore. But I like a little with my steak to cut the richness.” I take a sip.

Oh, god. Now it’s worse! Now, they could be thinking “Are we witnessing a relapse? Are we ’enablers’? Is he drinking to make us feel more comfortable and are we responsible for what happens next?!”

Sigh. Seems like any conversation about alcohol gets complicated quickly. There are tons of unspoken assumptions and guesses, and everyone lies about drinking… except those who don’t.

What to do? Well, mostly I don’t have the conversation. I just live my life. But when the conversation happens, it never feels like there’s enough space or trust or candor to have it fully, which is why I’m writing this. I want to lay out my journey with alcohol on the off chance that it resonates with some other people’s journeys. Because there are ways out of the quagmire of alcohol dependence that you maybe don’t know about. This was my way out.

The TLDR

We all hate the recipe sites where you have to scroll past a person’s life story just to get to the cornbread stuffing recipe. So I’ll stop right now and give you the particulars.

- I used a medication called naltrexone in a specific way (the Sinclair Method) that is scientifically and medically sound, but under-used

- This method actually relies on continued drinking while taking medication, and, it’s appropriate for people whose goal is moderation rather than sobriety

- I used an online community for support

- I ramped onto the medication very slowly because I had bad side effects the first time I tried it

Here’s the arc:

- Where I was: I was drinking most every night, and drinking a lot some nights. It was impacting my life

- My initial goal: Moderation. Social drinking. Not doing a gut renovation on my life

- What the pill did: Blocked my opiate receptors to take away some of the rewarding and self-reinforcing effects of drinking. I still got drunk

- How long it took: Binge drinking disappeared almost immediately, but reaching moderation took 10 months and no willpower (beyond taking the pill)

- Where I landed in 2021: Normal “social” drinking of a few drinks a few times a week

- Where I am now: 1-2 drinks per month, and I don’t miss it

So, yeah, I landed in a place that’s “sobriety-adjacent”… The 12-step crew would call this “not sober” but I don’t have much impetus to go the final mile. It’s just not a goal of mine. So why even go from moderation to near-sobriety? Last year, I used a sleep and fitness tracker for while. It showed me with data how much my body was affected by any alcohol at all. My sleep scores plummeted from one glass of wine, and my heart-rate-variability numbers took 72 hours to recover. This removed the last remnants of my desire to drink. On my moderation plateau, when offered a drink, the question was “Why not? I can handle it now, and only have one or two.” After seeing my health data, the question was “Why bother? It’s not worth three days of impact for a 30 minute buzz.”

But, if you’d asked me at the beginning of the above process whether fully quitting drinking was a desired outcome, I’d have said hell no. And I think that’s an important part of this story… which I guess I’ll go ahead and start…

Living in the Gap: Functional But Problematic

My drinking existed in that space between “fine” and “crisis”. Mostly fine. Sometimes in crisis. I was largely functional. I progressed in my career, maintained relationships, and appeared to have my life together. There were periodic episodes of trouble, but they were mostly private, not public.

I don’t want to give the impression that my drinking was sustainable. It was bad. It was really bad. The first version of this essay had a lot more data around exact drink counts, and publishing this has brought back memories of the cringe-inducing lengths I went to to hide the depth of my dependence on alcohol. I’ve decided to leave out drink counts and lurid tales, but it’s not pride. It’s strategy.

See, I want this effort to be relatable to a wide range of drinkers. If I was drinking more than you, and I probably was, you might think, “Well, I’m not that far gone, so I’ll just double down on willpower and get my shit together this time.” If I was drinking less than you, you might think, “Well, this might have worked for him, but I’m farther along.” And that would be a shame, because this is an effective and legitimate method of addressing alcohol dependence at many levels.

Even if your drinking patterns are sustainable, but you want to change them, the Sinclair Method still might be a good choice for you, so don’t stop reading.

I attended a couple of AA meetings and found myself in rooms filled with two distinct groups: long-timers who had their sobriety well in hand, and newcomers—some court-ordered—whose lives were in various states of disarray.

I have respect for AA long-timers, but I didn’t want to make the rest of my life about avoiding alcohol. The writing of this essay is the most I’ve thought about alcohol in years. I just wanted to get past it and stay past it. I also had concerns about the abstinence-only approach. Abstinence-based approaches can lead to a deprivation effect which can whiplash back into relapse. And relapses can be horrendous and damaging. The Sinclair Method was originally developed largely to address the deprivation effect of abstinence and its tendency to create catastrophe.

I’d watched people, including my own father, achieve success in AA only to experience devastating relapses that seemed more damaging than their original drinking. My own experiments with abstinence had shown me that the deprivation whiplash effect created intense rebound drinking.

I was genuinely terrified of getting sober for a short while only to relapse and destroy what was still a relatively stable life. The prospect of navigating complete social restructuring around sobriety felt overwhelming, too. I wasn’t looking to replace alcohol with a comprehensive lifestyle and spiritual overhaul. I wanted a solution that would address the unpredictability of my drinking while allowing me to maintain agency over my process.

Why not talk to my doctor? I did. I gave his way a shot and it didn’t work for me. I didn’t want to argue with him so I chose the online route for medication. If you’re wondering why your doctor might not know about this method either, see the epilogue on why this treatment remains under-studied and under-recognized.

First Attempt: Following the Rules (and Paying for It)

When I discovered the Sinclair Method, it seemed promising. The science made sense: naltrexone blocks the endorphin release that makes drinking rewarding, gradually reducing the brain’s association between alcohol and pleasure. Over time, this “pharmacological extinction” would reduce cravings and consumption. Reinforcement and reward… straight out of Psychology 101.

I got a scrip and followed the protocol exactly as described in the book I had bought. You start with half a tablet (25mg of naltrexone) 60 minutes before drinking sessions. Repeat that twice and then ramp onto a full dose. Simple, right?

Disaster… After a single half pill, I experienced four days of intense nausea, severe enough that I abandoned the method entirely. It turns out that there is science out there on initial side effects with naltrexone, though I believe it came out after the book I was reading had been printed. The study found that those who were able to cobble together a week of sobriety before starting naltrexone experienced much lower nausea and other side effects. This is why I’m not recommending the book I bought. The online Reddit community I found later maintains up-to-date info on the Sinclair Method. See the Resources section below.

This first failure is particularly bitter in retrospect. If I’d succeeded, I might have been able to help my father and family avoid years of suffering. My father was a heavy drinker all his life. He wasn’t a rage-filled alcoholic. He was just dependent and couldn’t seem to find a way out. He was a great candidate for Sinclair. He got a dementia diagnosis around the time I first tried Sinclair and failed. Lifelong drinking certainly contributed to his dementia, which was slow-moving. All told, he would be with us for another eleven years. The stress of losing his cognition and his usefulness accelerated his drinking and made everything about this awful disease even more awful.

I can barely stomach doing the math. If I’d succeeded with this first try, I would have been sober enought within a year or two. I could have advocated for the Sinclair Method and guided him through it while he was still sharp enough to manage it. Instead, he was sent to AA by his doctor, and when he relapsed was put on Antabuse until his cognition declined enough that it would be dangerous for him to stay on it. (Forgetting he was on Antabuse and drinking could have killed him, so they took him off.)

I considered trying to recommend Sinclair in 2021, after my second, successful attempt, but he was too far gone to manage something like that by then. By 2022, he was in a locked memory care.

He passed away this week.

Trying Again and Taking Ownership

Years went by. As my drinking patterns worsened over time, I eventually reached a point where I needed to try something again. I tried AA again and had the same issues. The Sinclair Method still seemed like the most logical approach for someone in my situation, if I could only get over the side effects. A week of sobriety felt out-of-reach for me at that point, so I had to adjust the protocols for my situation.

Instead of following the book’s dosing schedule, I decided to titrate onto the medication as slowly as possible. I got a new naltrexone prescription from an online doctor but didn’t involve them in my custom dosing plan. Taking matters into my own hands, I used a pill cutter and a 7-day pill organizer to break a single 50mg tablet into eight roughly equal pieces. The pill pieces were uneven, but this wasn’t a problem. I gulped down the smallest piece, and arranged the remaining pieces by ascending size in the pill organizer.

I was ready.

My titration plan was simple: one-eighth of a pill per day for eight days, then move to a quarter pill for four days, then half a pill, then the full Sinclair Method protocol. This two-week approach allowed my body to adjust without the severe side effects that had derailed my first attempt. It worked! I never felt any nausea with this method. The full dose pill sometimes gave me a slight feeling of dullness, maybe bordering on the mildest headache, but the alcohol soon made that go away.

Did I get drunk? Yes. Yes, I did. Regularly. But I stopped getting hammered. And the feeling of buzz and being drunk wasn’t much different from usual. In fact, once I was used to the Method, the couple of times I drank without waiting the recommended 60 minutes, I hated the woozy, dizzy feeling that unblocked alcohol had on my brain. From the online community, I understand that the most common reason for people giving up on the Sinclair Method is that they cannot get used to the feeling of drinking on the pill. They want that woozy buzz. For me, and most people, there’s not enough of a difference to notice or care.

The Immediate Gifts: An Upper Bound, and Mental Space

The reduction in the heaviest drinking days was noticeable and immediate. I would reach a point where I would just… stop drinking for the night. I just lost interest. I have never blacked out, but people in the online community often remark that blackout drinking stops immediately with this method.

That’s enough to recommend the Method, but the most profound early benefit was completely unexpected: I got my mental space back.

Before starting naltrexone, I hadn’t realized how much mental energy alcohol was consuming in my daily life. I was constantly engaged in alcohol-related thinking. I was planning how to drink as much as possible without getting detected, strategizing about how to resist drinking on certain days, trying to figure out how to control consumption at upcoming social events, researching homebrew projects, or just trying to resist the urge to drink.

This mental chatter was background noise I’d grown so accustomed to that I didn’t notice it until it stopped. I experienced a mental quiet that was remarkable. Suddenly, a significant portion of my cognitive bandwidth was freed up for other priorities in my life. I loved it. I have never been short of hobbies, projects, and ambition. Some people in my online community complained about being suddenly confronted by a life that had way more mental space than they were prepared to fill.

What Actually Happened: The Data

The Sinclair Method actually has three key parts: taking the pill, finding community, and tracking drinks. As a data nerd, I found this both easy, because I was used to tracking my habits, and challenging, because it was hard to be exact. I found myself quibbling over exact drink counts. For instance, one night I drank three 4% Bud Lights and an 8% IPA. Does that come out to four drinks or five? What about a 6.5% pale ale? What about a restaurant cocktail with a completely unknown amount of booze?

My solution: Round up and move on. For instance, I would call the above night a “6 pack night” even though it was clearly south of six drinks. If I went above six drinks, I called it a “12 pack night”.

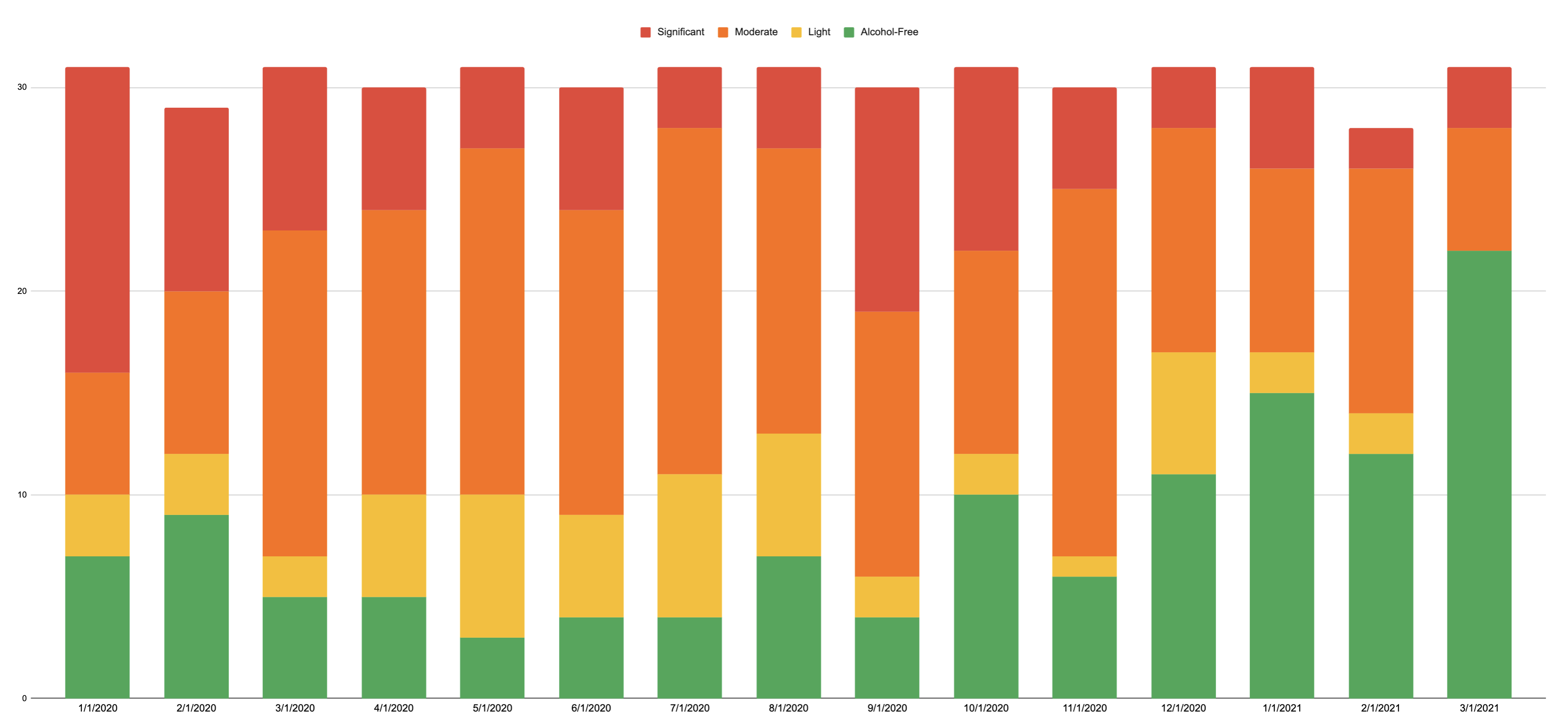

What I really wanted to know, and what I’m going to show you in the chart, is “What bucket did my drinking fall into for the day?” If you’re considering this method, I’d recommend to track drink counts, but rounding up to the nearest round number, whatever that looks like for you, is totally fine. Don’t get hung up on exact numbers. It’s a marathon not a sprint.

Here’s how my tracking played out. I’ve structured it monthly, and tallied how many days I spent in what bucket.

You can see that for the first nine months of the process, the changes in the data don’t seem significant. On the ground, however, everything changed. As mentioned above, the worst nights disappeared. Funnily enough, I had markedly fewer alcohol-free days after starting than before. Looking back, the pattern was clear. A binge would lead to a shame-based sober day or two. Fewer binges meant less shame, which meant fewer alcohol-free days.

The online community talks about a 1-2 month “honeymoon period” where your drinking plummets but doesn’t disappear, only to come roaring back. I didn’t have this. It would have been welcome to see big early progress, but also would have brought its own challenges.

I’m happy with how things played out. As I found more and more ability to stop drinking when I’d planned to, my self-respect grew.

You can see a big rebound in September 2020. Around this time people were talking about “Covid fatigue” where they’d been able to stand six months of lockdowns and chaos, but their internal reserves ran out in August or September. My therapist said at the time “Everyone on meds upped their dose in August 2020. They had just run through their reserves.”

You can also see starting around October that Light Drinking days started to be replace by Alcohol-Free days. Single-drink days were now in the “why bother” category. Why bother to take the pill if I was only going to have a single beer? It was easier to just forgo the beer and the pill.

Looking at this now, I can’t see much difference between the months. February and October look near-identical. September seems worse than unmedicated January. But when you’re both a binge drinker and a regular drinker, the real difference-maker is in those red bars. Those are the times you damage your self-worth, your relationships, your health.

In summary, this was not a hard year of tangling with sobriety and challenges, again and again. If I had been in AA, I would have been “working the program”, rebuilding my life, and navigating relapse. With the Sinclair Method, I got to muddle my way through Covid like the rest of society, but with more mental space and fewer binge-induced hangovers.

The Emotional Challenge: Losing Your Coping Mechanism

One of the weirdest experiences for me was the interim space when alcohol was no longer available to me as a coping mechanism, but I hadn’t yet developed other ways to cope with stress. An emotional challenge would come up for me, and my mind would reflexively consider alcohol to sooth it. Immediately behind that thought was another: “Wait, that won’t actually work.” This was the Sinclair Method beginning to work. Or rather, it was the combination of “pre-blocking” and “attempting anyway” that’s at the heart of the Sinclair Method beginning to show up. With Sinclair, a correctly structured drinking session is not considered a failure. The desire to drink is just a signal that alcohol is still a source of solace, and the rational response to that signal is to have a naltrexone-blocked drinking session.

But this part of it kinda sucked, to be honest. I think it was the biggest discomfort I felt in the whole process (except that initial nausea episode). There were many times when I desperately wanted something to help me with a difficult moment, and knew that alcohol couldn’t provide the relief I was seeking. This forced me to sit with emotions in a way I hadn’t done in years—mostly requiring me to tolerate discomfort without an easy escape hatch. This aspect came up regularly in online discussions, with some people criticizing the method as only addressing physical dependence without tackling emotional and spiritual aspects. I leaned on community through this process.

Looking back, I found it much easier to address the emotional and spiritual parts of my relationship with alcohol when that relationship wasn’t actively creating unpredictable chaos in my life. Emotional challenges will always arrive, but at least alcohol wasn’t creating excess challenges! The Sinclair Method doesn’t do the spiritual or emotional work for you. But it can create the stable foundation that makes that deeper work possible. It did for me.

Side note about weight loss: I did have a bit of a wake-up call late in my process. Other people in the online community kept posting about losing large amounts of weight by reducing their alcohol intake. Months into the method, I had dropped 5-10 pounds, but nothing life-changing. It was a sinking feeling to recognize, “Oh, alcohol might not be my only coping mechanism.” I did start to address my relationship with food later, and lost 40 pounds, but this is a good example of the benefit of this method. I would have failed outright if I’d tried to do the Sinclair Method while trying to lose weight at the same time. Unbundling worked wonders for me.

Also, in terms of coping mechanisms, online community is great, but it’s no substitute for a good therapist. I also had a great therapist and lots of emotional support throughout this process.

When Your Brain Finally Gives Up

The Sinclair Method works through “pharmacological extinction”. Your brain gradually stops expecting alcohol to provide pleasure and relief because naltrexone blocks those rewarding effects. But this process often takes much longer than you might expect and is often only visible in retrospect.

The extinction process was subtle. I detected a distinct shift in December 2020, but I couldn’t say what was shifting. My numbers just looked different. More alcohol-free days just started happening of their own accord. I didn’t need to force anything. It felt like a miracle. Everyone else was ramping up their holiday alcohol consumption and mine was ramping down… without effort.

Each week, each month, there seemed to be more alcohol-free days piling up. My internal desire to drink was no longer a driver of consumption. I was drinking only when external circumstances made it appropriate. This is also called “social drinking”.

By April 2021, I felt confident enough in this new relationship with alcohol that I stopped tracking consumption entirely. There was just not enough consumption to bother tracking. I still stayed 100% compliant with the pill, however. Patients who drink without naltrexone after reaching extinction return to former drinking patterns within weeks or months. It’s possible to return to naltrexone and re-reach extinction, but it’s harder and not guaranteed. For me, there was no point in risking one of the greatest gifts I’d ever been given.

One poster on the online forum mentioned that, after extinction, he had gone down to a half-dose of naltrexone if he knew he was only going to have one or two drinks. After long thought, I adopted this practice, but it’s not without risk. My new-found moderation felt like an absolute miracle. Risking it for the sake of a half a pill was a judgment call. I told myself that if I noticed any slide toward bigger consumption, I’d go back to the full pill and never mess with it again. Instead, things kept progressing toward non-drinking. I stayed with the half-pill method and my alcohol use continued to go down.

Community and Support: Finding My (Temporary) Tribe

Throughout this process, my primary support system was the r/Alcoholism_Medication subreddit. This online community focused on medication-assisted treatment provided what I needed: practical information, encouragement, and shared experiences.

What struck me about this community was the diversity of paths people took and the lack of judgment about different timelines. Some members achieved their goal of sobriety or moderation within months, while others, like myself, spent much longer at manageable drinking levels before reaching extinction. There was recognition that the medication works differently for different people and situations.

The community had also developed practical knowledge that wasn’t in the official literature, like starting with 5mg compounded naltrexone capsules for easier titration. No pill cutter needed. This peer-to-peer information sharing was invaluable for someone taking a non-standard approach to a non-standard method. They keep their resources updated as new information comes available, so I’m recommending it here as an uber-resource. I don’t want to send you to old science or outdated info. They have the best info and keep it up to date. Nice people, dedicated moderators, a supportive place. Check it out.

I checked in daily while I was on the Sinclair Method, often writing a ton. As I got past alcohol, I checked in less and less. Now I rarely go there. That’s the whole point of the Method. You solve your problem, alcohol is a non-issue in your life, you move on.

Current Perspective: A Stable Foundation for Growth

The Sinclair Method created the stable foundation from which I could address deeper emotional patterns around alcohol use and other reactive behaviors in my life. By removing the immediate unpredictability and chaos, it freed up mental and emotional energy to work on underlying issues from a position of stability rather than crisis. And it didn’t require me to completely upend my life to make these changes.

Today, I have a very occasional drink, on vacation or at social functions. I always return to my baseline without effort, though. In a given week, the most likely number of alcoholic drinks for me is zero. There is alcohol in my house, but it’s getting pretty dusty. After several years of this approach, I’m satisfied that there’s little risk of returning to the old patterns of problematic consumption. The pharmacological extinction process fundamentally changed my brain’s relationship with alcohol, making it possible to have an occasional drink without triggering the previous patterns. The unpleasant physical effects of that occasional drink, and the fleeting nature of the buzz I get from it, are enough to prevent any return to regular drinking.

Wait, What About Moderation?

Wasn’t moderation the goal, though? What happened to that? Should you be aiming for that? Was I kidding myself about aiming for moderation?

I came across this quote (from the Atlantic article I’ll link to below) about a physician who uses a mix of approaches, including targeted naltrexone, and who believes that moderation is a reasonable goal for some drinkers, but not all of them.

Moderate drinking is not a possibility for every patient, and he weighs many factors when deciding whether to recommend lifelong abstinence. He is unlikely to consider moderation as a goal for patients with severe alcohol-use disorder. (According to the DSM‑5, patients in the severe range have six or more symptoms of the disorder, such as frequently drinking more than intended, increased tolerance, unsuccessful attempts to cut back, cravings, missing obligations due to drinking, and continuing to drink despite negative personal or social consequences.) Nor is he apt to suggest moderation for patients who have mood, anxiety, or personality disorders; chronic pain; or a lack of social support.

I had a fair number of those DSM factors, and was digging out of a deep depression when I went back to the Sinclair Method. I was probably never a candidate for moderate drinking but, from the depths of my emotional dependence on alcohol, I needed to believe that I was. If you’d told me that the only reasonable long-term goal for my weekly drink count was zero, I would maybe have never even started. I needed the oasis of moderation hovering on the horizon, even if it was a mirage. When I got there, moderation didn’t look quite as inviting as it did from my original perspective, so I moved right along to… wherever it is that I am now.

As I write this on a fall afternoon, we’re booking our holiday travel. I’m always amazed at the difference between “vacation me” and “home me”. I don’t act differently on vacation, but when I get to the beach, I definitely cannot understand the choices I made when packing. I open my suitcase and think, “Who packed these bags and what was he thinking?!” Moderation was sort of like that. It seemed like an ideal destination for a different version of me, but by the time I arrived, I was different, so moderation was different.

Naltrexone gave me the ability to arrive at moderation, and keep right on moving. It might be a good destination for you. You can decide for yourself when you get there, and to me that’s a miracle.

– October 2025, Boulder, Colorado

Epilogue: Why You Haven’t Heard of This

Why you haven’t heard of this before? Nobody knows for sure. There’s all sorts of love-to-hate actors in this drama, like judges who mandate AA attendance for drunks, and Big Pharma and Big Rehab. But I don’t think there’s a concerted effort to bury this knowledge.

There’s been a couple of eruptions of naltrexone and the Sinclair Method into the public consciousness over the years.

There was a 2015 article in the Atlantic called “The Irrationality of AA”. It’s paywalled, but you can find a PDF linked below. Here’s a quote on why naltrexone is little-known:

Stephanie O’Malley, a clinical researcher in psychiatry at Yale who has studied the use of naltrexone and other drugs for alcohol-use disorder for more than two decades, says naltrexone’s limited use is “baffling.” “There was never any campaign for this medication that said, ‘Ask your doctor,’ ” she says. “There was never any attempt to reach consumers.” Few doctors accepted that it was possible to treat alcohol-use disorder with a pill. And now that naltrexone is available in an inexpensive generic form, pharmaceutical companies have little incentive to promote it.

Despite having a bunch of good information about the alternatives to AA, that article probably wouldn’t have been published in The Atlantic without the combative “AA is irrational” angle. It’s frustrating that we couldn’t learn about the Sinclair Method without also having to taking a few clickbait jabs at AA, but that’s the media.

I’ve got no beef with AA, except when people present it as the only way out of the drinking quagmire. I don’t know enough about AA from the inside to say for sure, but watching friends get sober via 12-step programs, I can guess as to why AA remains visible decade after decade, and the Sinclair Method remains little-known. Despite being anonymous and discreet, the way that people get sober with AA is more abrupt, both in starting abstinence and navigating relapse. Naltrexone allows people to change under the radar. My “relapse” of September 2020 was probably not detectable to anyone but myself. My father’s relapses from AA, on the other hand, often involved falling over in public.

People who succeed with the Sinclair Method just move on… And hopefully they move on to fixing the social, emotional, and spiritual wounds that led them to dependence… and that they accumulated while dependent. They get off booze slowly and quietly, and then they stop showing up on the online forum, and off they go. That’s what I did but I’m back because I felt a narrative like this was needed. I didn’t want to leave others behind.

Lastly, the most effective use of naltrexone is the Sinclair Method or “targeted dosing”. My primary doctor wasn’t aware of targeted dosing and rejected my suggestion of naltrexone based on reading abstinence-focused studies with daily dosing, a much less effective strategy.

There’s a lot of reasons doctors might not want to suggest it. They have to believe in the method, have to believe that you can handle it. They also take a leap of faith that recommending targeted dosing does not equal tacit approval of your continued drinking. If you walk out of their office, get drunk, get behind the wheel, and kill someone, they are going to wish they had said: “Take this gabapentin pill and resist drinking as strongly as you can,” instead of, “Take this naltrexone pill, wait an hour, and then drink as normal.”

So, yes, there are lots of reasons you might not have heard of this. If this essay has you wanting to try naltrexone, that might not be enough. You might have to convince others that this method is not delusional.

If your partner or doctor or parents think this naltrexone thing is too good to be true, and that you’re just latching onto something that will let you keep drinking, there’s a better resource than the Atlantic article. There’s a 2022 editorial from the American Journal of Psychiatry, a peer-reviewed medical journal, linked at the bottom. You can find a well-designed study of targeted dosing in the same issue. It’s short and to-the-point and will probably allay any concerns.

Resources

Alcoholism_Medication subreddit: https://www.reddit.com/r/Alcoholism_Medication/ Check the sidebar on that community for tons of resources, updated regularly

The Atlantic article: https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2015/04/the-irrationality-of-alcoholics-anonymous/386255/

A PDF version I found: https://soberlawnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/The-Irrationality-of-Alcoholics-Anonymous-The-Atlantic.pdf

The American Journal of Psychiatry editorial: https://psychiatryonline.org/doi/full/10.1176/appi.ajp.20220821

Me: If you want to talk to me directly about any of this, email me at myjourneywithalcohol@gmail.com